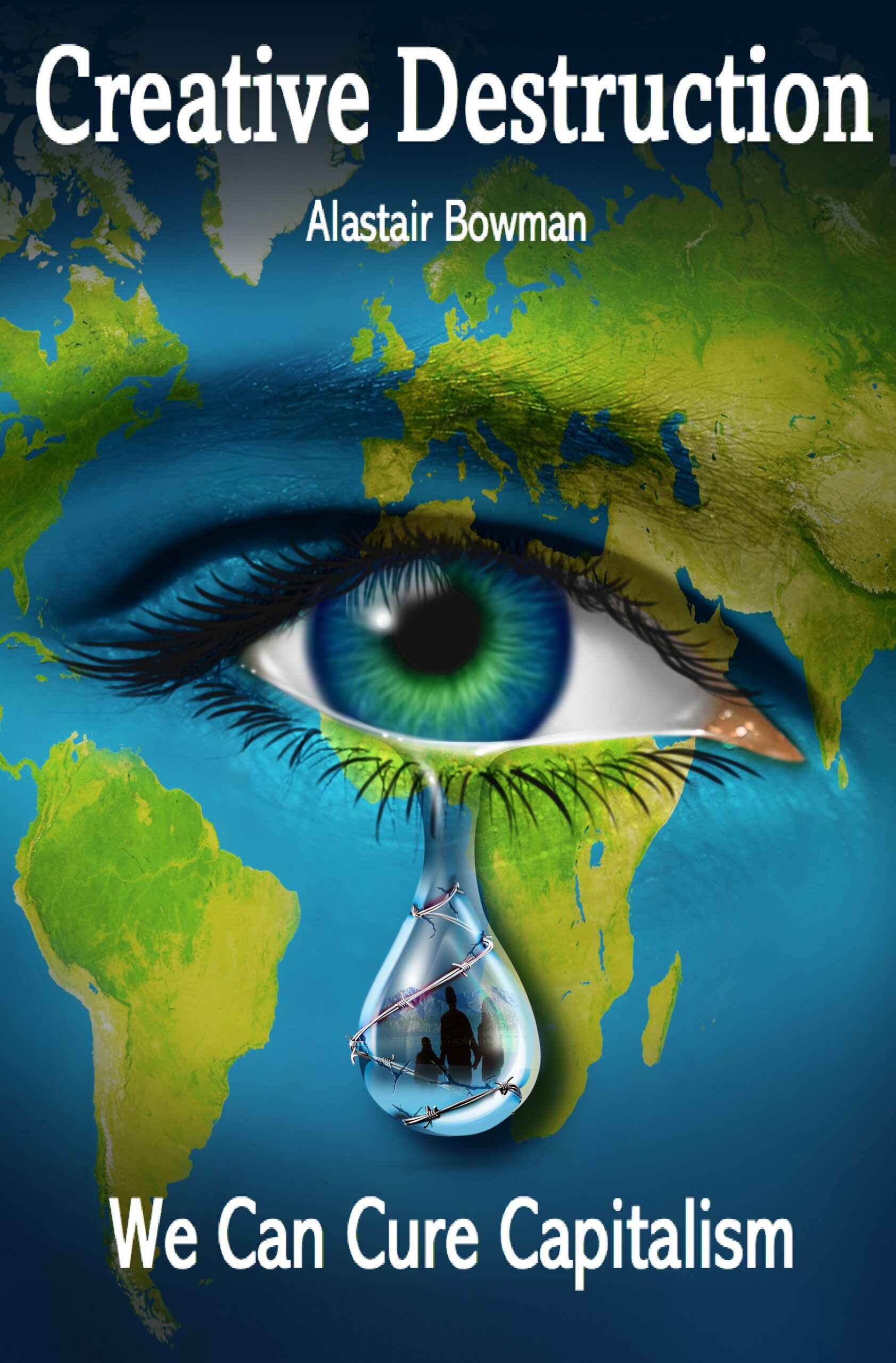

A central theme of my novel Creative Destruction is the difference between needs and wants, which are lumped together in modern economics as ‘demand’. The mechanics of supply and demand mean that poor people lose out.

The concept of ‘demand’ was developed in the 19th century but its roots lie in Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nation, published in 1776. He observed that people were highly motivated to improve their own lives, spurring social progress.

Smith believed that self-interest, combined with specialisation from a more complex division of labour, would unleash so much productivity and innovation that even the poorest benefit. He claimed that markets advantaged everyone, making them just and giving us permission to pursue our wants irrespective of other people’s needs.

Famously he wrote that markets are ‘led by an invisible hand’ though the end of that sentence is less widely cited: ‘to make nearly the same distribution of the necessaries of life, which would have been made had the earth been divided into equal portions among all its inhabitants’.

Does anyone seriously believe that? With the benefit of hindsight, we know he was wrong.

Today’s welfare state only exists because 19th century laissez-faire failed to address extreme poverty.

In reality, markets would fill a rich man’s swimming pool before quenching a poor family’s thirst, as happens in countless cities where there is great disparity between rich and poor and a free market in water.

Smith was right about the productive and innovative potential of capitalism, but he was wrong to claim that market outcomes advantage the poorest. He let us off the hook regarding the well-being of others, making selfishness consistent with the common good. This is highly comforting for those who do well, but if something is too good to be true, it usually is.

Yet the market is hugely powerful and we should use it while recognising its shortcomings. The key problem is that market prices favour the better off and fail the poorest most.

Markets can be liberating, challenging established hierarchies and empowering people with choices through free exchange. People facing acute need do not participate in this win-win.

On the supply side, all workers sell their produce or their time, but those trading to meet their basic needs are forced sellers. They must accept worse prices and lower wages because they have so little bargaining power.

When your children will go hungry or some other need will not be met, you are not just competing in the market but also racing against the clock, because needs get worse over time.

Many do not survive this race to the bottom. Those who do must tread water. They live to fight another day but cannot afford any advancement, or enjoy any choice, through which the rest of us progress.

A similar dynamic affects those on low incomes even where welfare assures their survival. Still, they spend a far higher proportion of their income on food, water, shelter and energy. There is little left over for any goods and experiences that might improve their lives or enhance their productivity. The better-off spend far more on wants, gaining those enhancements while poor people are left behind and inequality rises.

Markets allocate on price. The bargaining power at the heart of every transaction systematically favours the richer side.

Quite the opposite to ‘trickledown’, the bargaining power at the heart of every transaction means that money exerts its own gravity. It tends to mass into fortunes as market prices suck wealth up from the poorest.

As well as the gravitational pull of money, the price mechanism provides a second justification for redistribution.

We understand prices to work on diminishing marginal utility (DMU) – the more of something we have, the less we want more of it. An apple is nice, and I might even enjoy a second. But I’d pay less, the more they kept coming.

For decades, economic orthodoxy resisted the idea that DMU applied to money, arguing without foundation that money was a special case. That seems deeply self-serving when it merely tells the obvious truth that a pound is worth more to a pauper than to a millionaire. That makes a strong case for redistribution.

Adam Smith proclaimed the justice of market distribution because it improved the lot of the poorest. That is not true. Instead, market prices systematically favour the wealthy and redistribution is needed to maximise well-being. Still, markets are productive, innovative, and useful. We should use them, regulating where necessary to achieve democratically desirable goals.